Introduction

The purpose of this essay is to explore the ways in which educators can promote student agency and inquiry through the integration of technology. British Columbian educators have the responsibility of encompassing the Core Competencies in their pedagogy, meaning learners are constantly developing their thinking, communication, and personal and social skills. By engaging with the Core Competencies, students are granted a sense of agency when inquiring into the Big Ideas. Firstly, the theoretical framework will discuss the topic of sociocultural theory, and how the classroom environment acts as a society that shapes agentic learners. Next, we will draw upon constructivism to describe how students access prior knowledge to inquire into, and explore new content. Finally, we will discuss how multimodality explains the ways in which learners express their understandings, both through technology, and unplugged.

Theoretical Framework

Sociocultural theory

Sociocultural theory looks at how society contributes to the development of the individual. In looking at student agency through a sociocultural lens, learners are situated in complex and dynamic contexts that are mediated by individual actions, other learners, and the teacher (Vaughn, 2014, p. 7). The learning environment is a space where the teacher scaffolds learning, and students are active participants who engage with the context of the instructional situation. As such, learners are shaped by their participation and nonparticipation at school.

Constructivism

According to Piaget (1954), learners construct knowledge and develop an understanding of the world through their lived experiences. In connection with sociocultural theory, this meaning-making can take place individually or collaboratively. Within the constructivist framework, learning is viewed as an active process in which students are constructors, responsible for directing their own curiosities. Students access prior knowledge to grow an understanding about novel concepts, thus formulating their own perspectives and worldviews. In connection with inquiry-based learning, a constructivist perspective centers knowledge acquisition on exploration, invention and discovery.

Multimodality

Once students have constructed knowledge, multimodality theory recognizes the various avenues in which learners can communicate and express their learning through different forms of media. As stated by Kress (1997), “children act multimodally, both in the things they use, the objects they make; and in their engagement of their bodies: there is no separation of body and mind” (p. 92). The development of technology in the 21st-century has introduced new modes, means and materials through which learners can represent their knowledge. Consequently, this offers different “affective, cognitive and conceptual possibilities,” as noted by Kress. Student agency is honoured when educators value the voice of the child and advocate for learners to express their thinking through their chosen representation. In our current digital age, technology as a communication tool has the power to support, enhance and disseminate learners’ thoughts and ideas.

Student Agency

In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire (1970) viewed agentic learners as human beings who act upon their capacity to make a difference in their world. As aforementioned, student agency is socially-mediated and constructed. Instructional methods can either detract from or support children’s voices and interests. A study done by Vaughn (2014) looked at the role of the teacher in promoting that sense of agency, and data analysis indicated that in one classroom in the Southeastern region of the United States, opportunities for supporting and promoting student agency were overlooked by the educator. When educators do not hone in on meaningful, student-centred learning engagements, it “burries a lifelong learning stance and [sends] the message to students that their thoughts and actions are unimportant” (p. 13).

Why do some educators fail to honour student voice and choice?

Generally, classrooms are fast-paced environments where a large number of curricular topics are covered over the course of the day, and are fit into scheduled, time-constrained windows. During teacher formation programs, the pre-service teacher is advised to lesson plan down to the minute. This prescribed approach is then solidified through educational ministry guidelines, which can further limit opportunities to individualize student learning and to adapt the curriculum. In Vaughn’s (2014) study, the teacher in focus was constrained by standardized assessments and district-wide mandated curricula. The fact that she often “overlooked” student voice does not define her aptitude as a teacher, as within her school she was perceived as a strong educator with many years of experience.

Agency in BC classrooms

It is important to note that curricula around the world vary, and learners in our province are fortunate to explore a curriculum that promotes posing questions, interacting with others, and positioning oneself in their community and in society. These skills are done through the integration of the three Core Competencies which guide everyday instruction: Communication, Thinking, and Personal and Social, respectively (BC’s New Curriculum, 2016).

The role of technology in supporting student agency

With the flexibility of the BC Curriculum and the goals outlined within ADST among other subject matter, technology can be used to support or enhance students’ natural curiosity, ingenuity and inclination to create and work in practical ways (BC Ministry of Education, 2016). In the early years classroom, there is a lot of emphasis put on foundational literacy acquisition each day, and society’s conceptions of what it means to be literate has shifted over the past three decades. McLean (2013) argued that a mutually beneficial relationship exists between technology and literacy, and that we need to reconceptualize our perception so that technologies are viewed as conductors for communication (p. 31). The educator plays a role in mediating children’s use of, and experience with, technology, as acknowledged by sociocultural theory. Adults have the power to mediate language acquisition, and this can be done through the medium of technology (p. 31). When the agentic learner is provided with access to different communication tools that go beyond pencil, paper, and print media, their needs are able to be met in an individualized way. As such, technology is employed to substitute, augment, modify, or redefine how the learner communicates their thinking, based on Dr. Ruben Puentedura’s model of technology integration (“SAMR Model”, 2017).

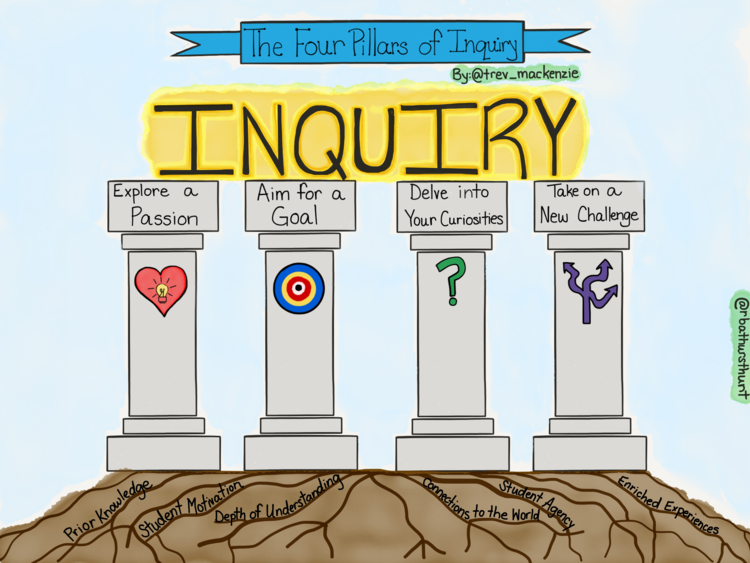

Inquiry-Based Model

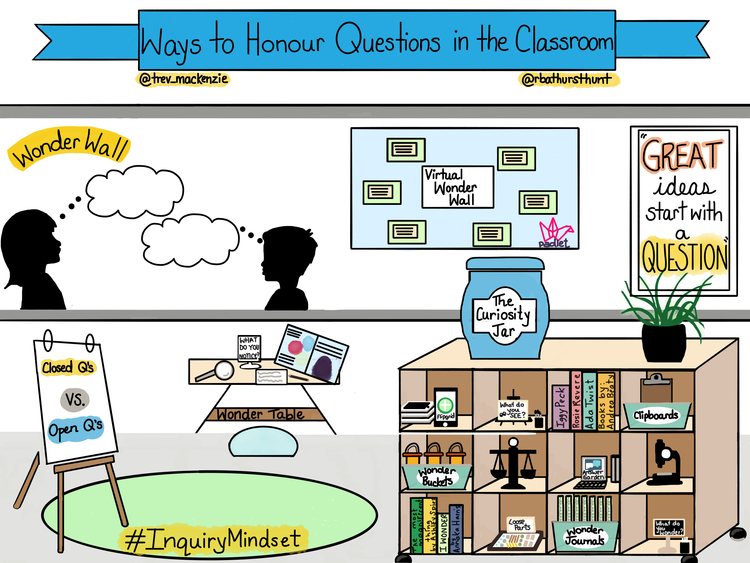

Within an inquiry-based approach, learners ask questions and explore their environment to better understand the world around them. Through the process of exploration, students develop a multitude of skills to enable them to become lifelong learners. Within this process, the educator’s role is to foster students’ questions in order to ignite young learners’ innate curiosity, so that it can continue to be cultivated and nurtured (Wang, Kinzie, McGuire, & Pan, 2010). Mackenzie and Bathurst-Hunt (2018) argued the importance of recording students’ questions as it creates a physical manifestation of a child’s wonder and displays our commitment as educators to honour their inquiries. Within inquiry-based learning, students are active members of the learning process, which means students construct their own knowledge as they explore and research any given topic. In comparison, within a traditional teaching model, information is disseminated to the learners directly from educators. This top-down approach to teaching negates the opportunity for students to develop various perspectives on given topics. An inquiry approach to education allows children to develop a richer understanding of the world and grants them the opportunity to construct their own meaning within the context of their life.

The role of technology in supporting student inquiry

Research has showcased the various benefits on child development when using technology to support inquiry-based education, including conceptual and cognitive development, literacy skills and mathematical reasoning (Wang et al., 2010). Technology provides students and educators with the unique opportunity to construct virtual models and representations of concepts that are challenging for young learners to conceptualize, such as the vastness of outer space (Gerald, Matuk & Linn, 2016). Through the use of such technological tools, students are able to represent their knowledge multimodally while also obtaining skills that promote higher-order thinking and metacognition.Wang et al. (2010) recommended that when considering which technology to incorporate within the inquiry process with young learners, the resources should “(a) enrich and provide structure for problem contexts, (b) facilitate resource utilization, and (c) support cognitive and metacognitive processes” (p. 382). Technology can be utilized to enhance tasks and provide a richer learning experience by offering more complex problems. When selecting technology resources, the available technology should not only facilitate access to various perspectives but additionally assist learners in efficiently locating and processing information from multiple sources. Gerald, Matuk & Linn (2016) additionally discussed how technology can be viewed as a partner for educators, by providing tools to follow students’ inquiries and their progression throughout their learning journey. Lastly, with the ability to track student progress, technology can also be used to streamline the assessment process by monitoring students learning formatively throughout their inquiries.

Conclusion

Based on the theoretical perspectives outlined, as well as the literature which has been drawn upon, student agency and inquiry are enhanced through the use of technological tools. The makeup of educational systems can influence educators’ capacities to provide a learning environment that is rich in student voice and choice. In BC, the curriculum is mandated to foster the development of critical and creative thinking skills so that learners can communicate their understanding by means of their chosen medium. The way in which communication takes place in BC schools can be enhanced and supported through the use of technology. Further, inquiry-based learning can be facilitated through resources that augment problem-solving contexts and foster metacognitive development. The interrelationship between agency, inquiry and technology creates a mutual, symbiotic process in which the student and educator learn collaboratively.

**This paper was written in collaboration with Emily Lacock.

References

BC’s New Curriculum. (2016). Retrieved from https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/competencies.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder.

Gerard, L., Matuk, C., & Linn, M. C. (2016). Technology as inquiry teaching partner. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 27(1), 1-9. doi:10.1007/s10972-016-9457-4

Kress, G. R. (1997). Before writing: Rethinking the paths to literacy. London;New York;: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203992692

MacKenzie, T., & Bathurst-Hunt, R. (2018). Inquiry mindset: Nurturing the dreams, wonders, and curiosities of our youngest learners. Irvine, California: EdTechTeam Press.

McLean, K. (2013). Literacy and technology in the early years of education : Looking to the familiar to inform educator practice. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 38(4), 30-41. doi:10.1177/183693911303800405

Piaget, J., 1896-1980. (1954). The construction of reality in the child. New York: Basic Books.

SAMR Model: A Practical Guide for EdTech Integration. (2017, October 30). Retrieved from https://www.schoology.com/blog/samr-model-practical-guide-edtech-integration.

Vaughn, Margaret. (2014). The role of student agency: Exploring openings during literacy instruction. Teaching and Learning: The Journal of Natural Inquiry & Reflective Practice. 28. 4-16.

Wang, F., Kinzie, M. B., McGuire, P., & Pan, E. (2010). Applying technology to inquiry-based learning in early childhood education. Early Childhood Education Journal, 37(5), 381-389. doi:10.1007/s10643-009-0364-6

Recent Comments